Some Small Useful Features of GitHub Actions

Due to recent problems free CI servers have had with abuse from cryptocurrency miners, Travis CI are scaling back what services are available to open source projects. We used to use Travis for QuTiP, but the new pricing model has meant that we won’t be able to afford it once the old free tier travis-ci.org completely shuts down. We trialled GitHub Actions to build the 28 different wheels we now distribute on PyPI, and then moved all our testing there as well.

Here are few nice features that I’ve been using since we started. These are mostly not unique to GitHub Actions, but all my example configuration code will be for it.

Manually triggered workflow runs with user inputs

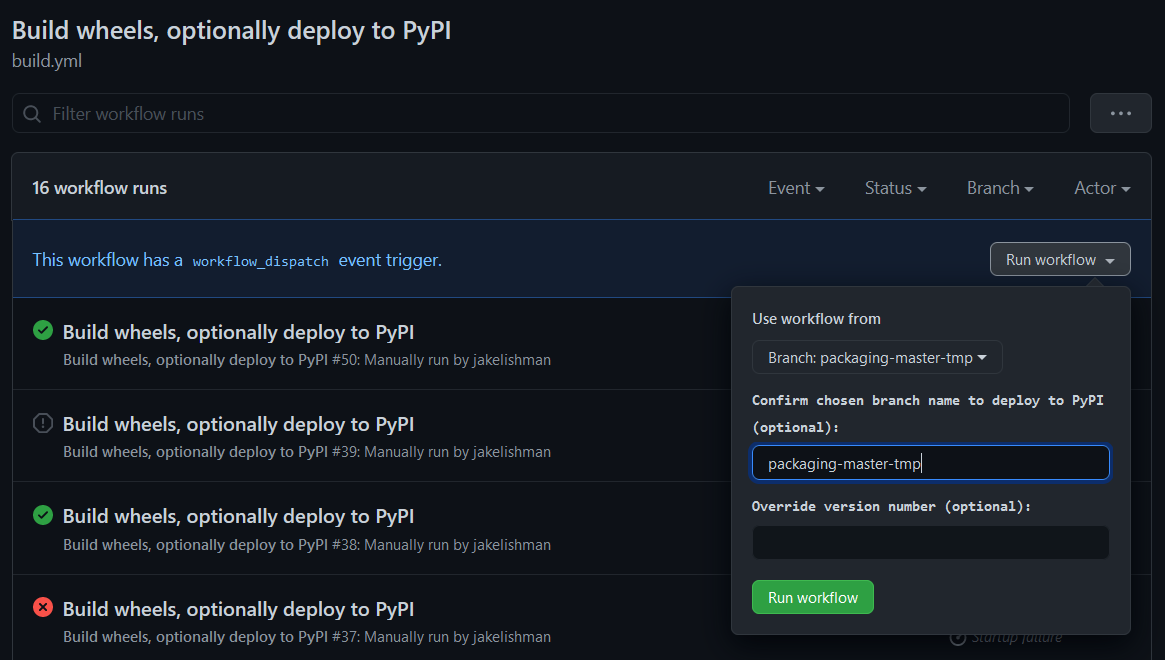

On shared servers which integrate with GitHub, usually workflow runs are only triggered on pull requests or pushes to particular branches. Since we distribute prebuilt C extensions over all three major OSes and 4 minor CPython versions, we have quite a lot of wheels to build and test on a given run. The workflow_dispatch trigger on GitHub Actions is great for us, because it gives us an easy way to manually trigger a run so we can build the full distribution for any GitHub reference or commit we want. We also use inputs to the actions with this trigger, to implement a user confirmation and to allow deploying with version-number overrides.

This is simple to do; here’s an example from the QuTiP distribution workflow:

name: Build wheels, optionally deploy to PyPI

on:

workflow_dispatch:

inputs:

confirm_ref:

description: "Confirm chosen branch name to deploy to PyPI (optional):"

default: ""

override_version:

description: "Override version number (optional):"

default: ""This gives us a nice user interface for the administrator as well:

We use the confirm_ref input as a way to make sure the deployment will certainly be done from the correct code state, by asking the administrator to type in the branch name and make sure it matches the selected branch. We have the very first subjob be a very simple bash test of this:

deploy_test:

name: Verify PyPI deployment confirmation

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

env:

GITHUB_REF: ${{ github.ref }}

CONFIRM_REF: ${{ github.event.inputs.confirm_ref }}

steps:

- name: Compare confirmation to current reference

shell: bash

run: |

[[ -z $CONFIRM_REF || $GITHUB_REF =~ ^refs/(heads|tags)/$CONFIRM_REF$ ]]and all subsequent jobs have a needs: deploy_test instruction to make sure everything fails as fast as possible. This also uses GitHub Actions’ very flexible dependency graph for jobs.

Sparse configuration matrices

The main QuTiP library has several optional dependencies, and has special routines when compiled with OpenMP, or linked against different BLAS/LAPACK implementations. For some of our optional dependencies, especially run-time compilation of time-dependent coefficients in ODEs, we provide fallback pure-Python implementations to make sure that the same code will run regardless. It isn’t necessary, or even really possible, for us to test every single combination of supported Python version, installed optional dependencies and BLAS implementations, but GitHub Actions’ implementation of configuration matrices lets us add in special cases which only specify some of the switches.

For example, GitHub Actions lets us create a job matrix with the normal combinations and then add in additional special cases. We can define some extra parameters in these special cases, and act on them later in the runners. These parameters can have any names we choose, and aren’t bound to certain values. Here is QuTiP’s main testing matrix specification:

name: ${{ matrix.os }}, python${{ matrix.python-version }}, ${{ matrix.case-name }}

runs-on: ${{ matrix.os }}

strategy:

fail-fast: false

matrix:

os: [ubuntu-latest, macos-latest, windows-latest]

python-version: [3.9]

case-name: [defaults]

# Extra special cases.

include:

- case-name: old SciPy

os: ubuntu-latest

python-version: 3.6

scipy-requirement: ">=1.4,<1.5"

- case-name: no MKL

os: ubuntu-latest

python-version: 3.7

nomkl: 1

- case-name: OpenMP

os: ubuntu-latest

python-version: 3.9

openmp: 1

- case-name: no Cython

os: ubuntu-latest

python-version: 3.8

nocython: 1We add extra parameters scipy_requirement, nomkl or such on, and then our bash dependency install job looks like

QUTIP_TARGET="tests,graphics,semidefinite"

if [[ -z "${{ matrix.nocython }}" ]]; then

QUTIP_TARGET="$QUTIP_TARGET,runtime_compilation"

fi

export CI_QUTIP_WITH_OPENMP=${{ matrix.openmp }}

if [[ -z "${{ matrix.nomkl }}" ]]; then

conda install blas=*=mkl numpy "scipy${{ matrix.scipy-requirement }}"

elif [[ "${{ matrix.os }}" =~ ^windows.*$ ]]; then

pip install numpy "scipy${{ matrix.scipy-requirement }}"

else

conda install nomkl numpy "scipy${{ matrix.scipy-requirement }}"

fi

python -m pip install -e .[$QUTIP_TARGET]

python -m pip install pytest-cov coverallsWe use the ${{ }} GitHub Actions syntax to insert the parameter value, using the fact that a missing parameter silently evaluates to nothing, and standard tests [[ -z "${{ ... }}"]] to test for emptiness. One minor inconvenience is the need to have special parameters for which a set value corresponds to truth, so we have openmp=1, but nomkl=1 rather than mkl=0. We could work around this by changing the response to unset variables in certain cases, but neither solution is entirely satisfying, so we stick with the simpler one.

Conditional steps

The syntax of the workflow files includes some small rudimentary programming constructs and conditional execution. You can well argue that this might not be a good thing (e.g. one, two), but right now it is what we have, and if we don’t go overboard, it can be useful.

One use-case we have for this is in qutip-qip, which is the soon-to-be separate quantum information processing module of QuTiP. With it now being developed separately, it is not tied to any particular version of the main library, and it needs to work with many, including ones that are not even published yet. We can achieve this using the regular matrix syntax:

strategy:

matrix:

qutip-version: ['>=4.6,<4.7', '@master', '@dev.major']

steps:

install-pypi:

name: Install QuTiP from PyPI

if: ${{ ! startsWith(matrix.qutip-version, '@') }}

run: pip install 'qutip${{ matrix.qutip-version }}'

install-git:

name: Install QuTiP from GitHub

if: ${{ startsWith(matrix.qutip-version, '@') }}

run: pip install 'git+https://github.com/qutip/qutip.git${{ matrix.qutip-version }}'We set the qutip-version parameter either to a pip specification (>=4.6,4.7') or a git reference on the qutip/qutip repository (@master, @dev.major). The @ is not part of the reference itself, but the pip install git+ command interprets it as the separator. This sort of switching can be done with standard bash, but we can also use the conditional step structures to give us better naming when monitoring the action.

if: ${{ startsWith(matrix.qutip-version, '@') }}tests that only the chosen job will run, so we only get the relevant name appear. This just makes it a little easier to see at a glance which steps were taken.

These are all fairly simple features, but ones I’ve found useful to make our processes easier to use and understand. I’m still learning as I go with many parts of DevOps, so maybe I’ll change my mind as to what is the best practice in the future, though so far these strategies have really simplified a lot of our build and deployment cycle for QuTiP.